Legal System and Research in Portugal

By Raquel Ferreira Pedrosa Alves

Raquel Ferreira Pedrosa Alves is a Portuguese lawyer registered at the Portuguese Bar Association since 2005. Currently, Raquel is a Senior Legal Adviser working in the fields of administrative law, public procurement, corporate law, and compliance at Transportes Metropolitanos de Lisboa. She is responsible for managing the public road transport service in Lisbon Metropolitan area and the technological platform integrating the ticketing and public information system, as well as for developing studies and plans and implementing accessibility, mobility, and transport policies. Previously, she worked as a Regulatory & Legal Adviser in the areas of administrative and public law, regulation, electronic communications, e-commerce, and space law at Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações (ANACOM)/National Communications Authority in Portugal.

Raquel earned her LL.B. from the Faculty of Law at Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugal (1998-2003) and Advanced LL.M. in International Business Law from Católica Global School of Law, Portugal and Duke University School of Law, USA (2015/2016). She also earned post-grade course of Law & Medicine from the Institute of Criminal Law and Criminal Sciences of Faculty of Law at Universidade de Lisboa, Portugal (2017) and Master’s Degree in Transnational Law from Universidade Católica Portuguesa − Lisbon School of Law, Portugal (2017-2019) with a master thesis titled “Advance Directives–What Can We Learn from the American Advance Care Model?” Between 2007 and 2015, Raquel lived and worked in Macau Special Administrative Region of People’s Republic of China as an Associate Lawyer in a Luso-Chinese law firm, and later as a Legal Adviser at the Macau Government Health Bureau. Raquel is a permanent resident of Macau and is registered at the Macau Lawyers Association.

Published May/June 2025

(Previously updated by Tiago Fidalgo de Freitas in December 2009; by José Caramelo Gomes and Sérgio Tomás in May/June 2014; and by Raquel Ferreira Pedrosa Alves in July/August 2020)

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Sovereign Bodies

- 2.1. The President of the Republic

- 2.2. The Assembly of the Republic

- 2.3. The Government

- 2.4. The Judiciary

- 3. Independent Regulatory Authorities

- 4. Sources of Law

- 5. Main Legislation

- 6. Legal Professions and Organizations

- 7. Legal Education and Law Universities

- 8. Research Databases

- 9. Bibliography

1. Introduction

Portugal is one of the oldest countries of the European Continent, whose independence dates back to 1143.[1] It is located on the Iberian Peninsula and is the westernmost country in Europe. Lisbon city is the capital. Besides its continental land, the territory of the country comprises two archipelagos in the Atlantic Ocean, named the Autonomous Region of Azores and the Autonomous Region of Madeira, that enjoy a substantial degree of administrative autonomy.[2] The official language is Portuguese. According to Pordata Database, Portugal (2023) has over 10.6 million inhabitants.

Portugal became a republic in the year of 1910. A dictatorship, which lasted almost half a century (from 1926 to 1974), ended with the revolution of April 25, 1974, also known as the Carnation Revolution (Revolução dos Cravos), which established a democracy in the country. The 1974 revolution started the decolonization process in what was once Portuguese Africa, ended the Colonial War, and led to the independence of the former Portuguese colonies of Angola, Mozambique, and Guinea-Bissau. Later, other overseas territories/regions under the Portuguese administration, like Macao, passed to the People’s Republic of China in 1999, and Timor-Leste became independent in 2002.

For more than forty years, Portugal has been a stable parliamentary republic ruled by the Portuguese Constitution, which was adopted in 1976. The new Constitution provides for a wide range of fundamental rights (e.g., civil, political, economic, social, and cultural) and guarantees a democratic and multi-party regime, based on the principles of the dignity of the human person and on the free will of the people.

As stated in article 2 of the Constitution, the Portuguese Republic is “a democratic state based on the rule of law, the sovereignty of the people, plural democratic expression and political organization, respect for and the guarantee of the effective implementation of the fundamental rights and freedoms, and the separation and interdependence of powers, with a view to achieving economic, social and cultural democracy and deepening participatory democracy.”[3]

Portugal became a member of the United Nations in 1955 and a member state of the European Union (EU) in 1986.[4] It had signed the Schengen agreement in 1991 and started its implementation in 1995. On January 1, 1999, Portugal adopted the Euro as its currency. See the European Commission’s report, Portugal and the Euro. Portugal is also a member of several international organizations, such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP).

2. Sovereign Bodies

Portugal has the following sovereign bodies:

- The President of the Republic (PR − Presidente da República), which is the Head of State.

- The Assembley of the Republic (AR–Assembleia da República), which represents all Portuguese citizens and has the legislative power.

- The Government (Governo), headed by the Prime Minister and that mainly deals with political, legislative, and administrative matters.

- The Courts (Tribunais), which exercise the judicial power, being totally independent from the other branches of power.

The separation of powers among the sovereign bodies of state is guaranteed by article 111 of the Portuguese Constitution.

2.1. The President of the Republic

The President of the Republic is elected by universal, direct, and secret suffrage. The mandate of the President is for five-years, and they can be re-elected only once (articles 121, 123, and 128 of the Constitution). According to article 120 of the Portuguese Constitution, “[t]he President of the Republic represents the Portuguese Republic, guarantees national independence, the unity of the state and the proper operation of the democratic institutions, and is ex officio Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces.”

When necessary, the President may use the right of promulgation and the power of veto over legislation (article 136). They also have the power to dismiss the Government and to the dissolve the Parliament (article 133). Competences of the President include, among others, to submit issues of relevant national interest to a referendum, to declare the state of siege or a state of emergency, to grant pardons, commute sentences, and request the Constitution Court to examine the constitutionality of norms (article 134).

In terms of international relations, as per article 135 of the Constitution, the President appoints ambassadors, ratifies duly approved international treaties, and declares war after the Government proposal and consultation of the Council of State, including with the authorization of the Assembly of the Republic.

The President is advised by the Council of State (article 141). According to article 145 of the Constitution, the Council of State should be summoned by the President should he decide, among others, to dissolve the Assembly of the Republic, dismiss the Government, or declare war or peace.

2.2. The Assembly of the Republic

The Assembly of the Republic is Portugal’s unicameral parliament. Presently, it is composed by 230 members (deputies), who are elected by a universal, direct, and secret suffrage for a four-year term of office (articles 148 and 149 of the Portuguese Constitution). The national parties at the Portuguese Parliament, as of 2024 elections, are the following: PPD/PSD − People’s Democratic Party/Social Democratic Party) (eighty deputies), PS − Socialist Party (seventy-eight deputies), CH − Enough (fifty deputies), IL − Liberal Initiative (eight deputies), BE (Left Bloc) − (five deputies), PCP − Portuguese Communist Party (four deputies), L − FREE (four deputies), PAN − People-Animals-Nature Party (one deputy). See the official chart with the result of the elections.

The Assembly of the Republic has competences to legislate alongside other bodies on all other matters, except those regarding the organization and functioning of the Government. It has competences to pass amendments to the Constitution, to pass political and administrative statutes of the Autonomous Regions, and to approve the State Budget and others (article 161). In accordance with article 162 of the Constitution, the Assembly of the Republic also has the competences of scrutinizing the activity of the Government and the Administration, as well as ensuring compliance with the Constitution and laws.

In addition, it has exclusive legislative competence for matters determined in the Constitution, such as elections, referendums regimes, Constitutional Court organization, national defense organization, legal regimes on the state of siege and state of emergency, acquisition and loss of Portuguese citizenship, definition of the limits of territorial waters, the exclusive economic zone, the rights of Portugal to the contiguous seabed, associations and political parties, and the legal framework of the education system (article 164).

Partially exclusive legislative competences of the Assembly of the Republic are established in article 165 of the Constitution, which include, among other matters, the following: people’s legal status and capacity, rights, freedoms and guarantees, definitions of crimes, sentences and security measures, general regime/governing, the punishment of disciplinary infractions and administrative offences, general regime governing requisitions and expropriations, the basis of social security system and the national health service, protection of nature and cultural heritage, creation of taxes and fiscal system, the basis of the agriculture policy and the monetary system, the organization and competences of the courts, and the statutes governing local authorities.

2.3. The Government

Under article 182 of the Portuguese Constitution, “[t]he Government is the body that conducts the country’s general policy and the supreme authority in the Public Administration.” The Government is headed by the Prime Minister and is comprised by the Ministers (that meet in the Council of Ministers), Secretaries, and Under Secretaries of State. One or more Deputy Prime Ministers may also be included (article 183). The Prime Minister is appointed by the President of the Republic after consulting with the parties with seats in the Assembly of the Republic and in the light of the electoral results. The remaining members of the Government are appointed by the President of the Republic upon proposal of the Prime Minister (article 187).

The Government has political, legislative, and administrative competences. In accordance with article 197 of the Constitution, the Government has competences to negotiate and conclude international conventions, to approve international agreements outside the scope of the Assembly of the Republic, to submit bills to the Assembly of the Republic, to propose to the President of the Republic that matters of important national interest be subject to referendum, to pronounce on the declaration of stage of siege or state of emergency, etc.

In respect to the legislative competence, as per article 198 of the Constitution, the Government can legislate over matters that do not fall within the exclusive competence of the Assembly of Republic and on maters that fall within the Parliament partially exclusive competence subject to authorization of the latter. Moreover, the Government has competences to make laws that develop the principles or the basic general bases of acts of the Assembly of the Republic. The Government has the exclusive competence to legislate on matters concerning its own organization and functioning.

Currently, the Government in office (Government XXV) upon 2025 Elections is composed by the Prime Minister and a total of sixteen Ministers. See the current Government composition: XXV Constitutional Government.

2.4. The Judiciary

According to article 202 of the Portuguese Constitution, “[t]he courts are entities that exercise sovereignty with the competence to administer justice in the name of the people.” The courts are also “responsible for ensuring the defense of those citizen’s rights and interests that are protected by law, repressing breaches of democracy legality and deciding conflicts between interests, public and private.” Article 203 of the Constitution establishes that “courts are independent and subject only to the law.” According to article 205, “court decisions are binding on all public and private entities and prevail over the decisions of any other authorities.”

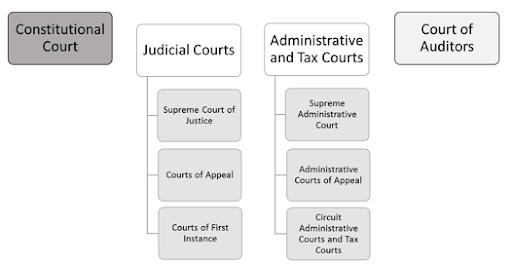

Moreover, court hearings are held in public, save when the court decides otherwise–in order to safeguard personal dignity or public morals or to ensure its own proper functioning–by way of a written order setting out the grounds for its decision (article 206). As per article 209 of the Portuguese Constitution, in Portugal, there are several categories of courts (see TRIBUNAIS.ORG, Os Tribunais) as follows:

- The Constitutional Court is composed of thirteen judges and whose main task consists of assessing the constitutionality or legality of law and norms, as well as the constitutionality of a failure to legislate (articles 221 to 223)

- The ordinary judicial courts (see TRIBUNAIS.ORG, Judicial) with civil and criminal jurisdiction are organized in three instances: the Supreme Court of Justice with nationwide jurisdiction, the second instance courts (five courts of appeal−Tribunais da Relação: Lisboa, Porto, Coimbra, Guimarães, and Évora), and the courts of first instance (district courts−Tribunais de Comarca, with specialized competence in different subjects, including criminal law, family and juvenile law, labor law, commercial law, maritime, and the enforcement of penalties) (articles 210 and 211)

- The administrative and tax courts (see TRIBUNAIS.ORG, Administrativo e Fiscal) whose function is to settle disputes arising out of administrative and tax relations, include the Supreme Administrative Court with jurisdiction over whole country; the central administrative courts (courts of appeal, i.e., the Northern Central Administrative Court and Southern Central Administrative Court−Tribunais Centrais Administrativos Norte e Sul); the first instance courts, i.e., circuit administrative courts (Tribunais Administrativos de Círculo); and the fiscal courts (Tribunais Tributários) (article 212)

- The Court of Auditors is the highest body with the authority to scrutinize the legality of public expenditure and to review the accounts that the law requires to be submitted to it (article 214)

- The maritime courts, arbitration tribunals, and justices of the peace (article 209, number 2).

In Portugal, there is one maritime court, located in Lisbon, with competence over all the continental territory. The justices of the peace are courts with competence in civil proceedings where the value of the claim does not exceed €15,000. For more information on arbitration and justice of the peace, see JUSTIÇA.GOV.PT, Resolução de litígios.

Furthermore, the law shall determine the cases and forms in which the foregoing courts may form separate or joint tribunals of conflict. Without prejudice to the provisions on military courts (article 213 of the Constitution), which may be created during the period of war with competence on crimes of military nature, the existence of courts with exclusive jurisdiction for the prosecution of certain categories of crime shall be prohibited (article 209, nos. 3 and 4 of the Constitution).

Diagram 1: Structure of the Portuguese Courts

An additional note to mention that the Public Prosecution Service (Ministério Público) is a body within the system of the administration of justice and part of the judicial branch of the State. It constitutes a magistracy similar to that of the judiciary but separate from and independent of it. Like the judges, public prosecutors are magistrates. Despite being part of the judiciary, the Public Prosecution Service is autonomous, having its own Law no. 68/2019, of August 27 (amended by Law no. 2/2020, of March 31) and broad powers of initiative.

As per article 219 of the Constitution, the “Public Prosecutors’ Office has the competence to represent the state and defend the interests laid down by law, and (…) to participate in the implementation of the criminal policy defined by the entities that exercise sovereignty, exercise penal action in accordance with the principle of legality and defend democratic legality.” In a nutshell, its purpose is to guarantee the right to equality before the law and full compliance with the laws according to democratic principles.

3. Independent Regulatory Authorities

As in many European countries, in Portugal, there are a wide range of independent regulatory authorities with administrative and financial autonomy that play an important role in regulating different sectors of the economy−such as financial and insurance sectors, energy, communications and media sectors, competition policy, and health care−in order to ensure fair competition, as well as to safeguard certain fundamental rights and to protect consumer’s rights and interests.

These authorities started emerging in the 1990s, and their creation resulted from the need to effectively enforce national laws implementing EU market liberalization legislation.[5] There are several independent regulatory authorities in Portugal, the main of which are the following:

- Bank of Portugal (Banco de Portugal)[6] responsible for supervising credit institutions, financial companies, and other entities subject to it by law, which core missions are to maintain price stability and ensure the steadiness of the financial system

- Energy Services Regulatory Authority (ERSE − Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos) responsible for regulating the electricity and natural gas sectors

- National Authority for Communications (ANACOM − Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações) responsible for the regulation and supervision of postal and electronic communications sector

- National Authority of Medicines and Health Products (INFARMED − Autoridade Nacional do Medicamento e Produtos de Saúde) responsible for evaluating, authorizing, regulating, and controling human medicines, as well as health products, namely medical devices and cosmetics for the protection of Public Health

- Civil Aviation Authority (ANAC − Autoridade Nacional da Aviação Civil) responsible for the civil aviation sector

- Competition Authority (AdC − Autoridade da Concorrência)[7] responsible for economic market regulation and for insuring compliance with the competition rules

- Data Protecion Authority (CNPD −Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados) responsible for supervising and monitoring compliance with the laws and regulations in the area of personal data protection

- Healthcare Regulation Authority (ERS − Entidade Reguladora da Saúde) responsible for regulating the activity of health care providers

- Insurance and Pension Funds Supervisory Authority (ASF − Autoridade de Supervisão de Seguros e Fundos de Pensões) responsible for regulating and supervising the activity of insurance, reinsurance, pension funds and their management entities, and insurance mediation

- Regulatory Authority for the Media (ERC − Entidade Reguladora para a Comunicação Social) responsible for media content regulation

- Secutiries Market Commission (CMVM − Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários) responsible for supervising and regulating the financial instruments and the agents operating within those markets and promoting investor protection

- Water and Waste Services Regulation Authority (ERSAR − Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços de Águas e Resíduos) responsible for regulating and supervising the public water supply, urban wastewater, and urban waste management sectors

- National Anto-Corruption Mechanism (MENAC − Mecanismo Nacional Anticorrupção) responsible for monitoring and sanctioning offences against the General Regime for the Prevention of Corruption (Regime Geral da Prevenção de Corrupção) and the General Regime for the Protection of Whistleblowers (Regime Geral de Proteção de Denunciantes de Infrações)

Law no. 67/2013, of August 28 last amended by Law no. 75-B/2020, of December 31) is the framework law for independent regulatory entities that regulate economic activity in the private, public, and cooperative sectors. It establishes rules on the nature, role, creation, governance, and functioning of these entities. As per article 3, number 1 of the Framework Law, these bodies are defined as “public law bodies with the nature of independent administrative entities, responsible for regulating economic activity, defending services of economic interest, protecting consumer’s rights and interests and promoting and defending competition in the private, public, cooperative and social sectors.” Despite the efforts in establishing a common institutional regime applied to all regulatory entities or authorities, there are several regulators not covered by the Framework Law, which is the case, for example, of the Bank of Portugal, ERC, and INFARMED.[8]

4. Sources of Law

Statutory law (lei) is the primary source of law in the Portuguese legal system (article 1, number 1 of the Civil Code). A “law” is defined as a generic rule enacted by the bodies with legislative powers, which according to the Portuguese Constitution, are the Assembly of the Republic, the Government, and the Legislative Assemblies of each autonomous region of Azores and Madeira.

As per article 5 of the Civil Code, laws shall be binding only after their publication in the Portuguese Official Gazette. Once a law has been published, it shall enter into force after the period stipulated in the law itself has elapsed or, where no such period is stipulated, after the period provided for in special legislation. Laws remain in force until they are revoked by another law. Number 2 of Article 7 of the Civil Code states that “[r]evocation may arise from an express declaration, from incompatibility between the new provisions and the preceding rules, or from the circumstance that a new law regulates all matters covered by a preceding law.”

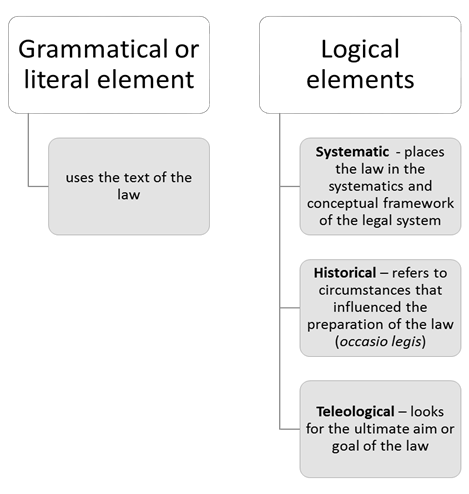

The general principle is that the law only provides for the future. Even if a retrospective effect is granted to the law, it shall be presumed that the effects already produced are not affected by the facts that the law intends to regulate (article 12, number 1 of the Civil Code). Legal interpretation aims to determine the meaning and scope of norms through the application of hermeneutical methodology. It takes into consideration the grammatical and logical interpretation elements, as prescribed in article 9 of the Civil Code.

The grammatical or literal element (elemento gramatical/literal) uses the plain and ordinary meaning of the words (the text of the law). However, the interpretation shall not be limited to the text of the law. The grammatical element of interpretation is complemented by the logical element (elemento lógico) of interpretation, which in turn includes the systematic, historical, and teleological elements.

The systematic element (elemento sistemático) places the law in its context, that is the systematics and conceptual framework of the legal system. The historical element (elemento histórico) refers to the political, social, and economic circumstances that influenced the preparation of the law (occasio legis). The intention of the legislator vis-à-vis such circumstances can be found, for example, in the preparatory works, previous drafts, and materials that led to the promulgation of the law. The teleological element (elemento teleológico) refers to the ultimate purpose or goal of the law. The leading considerations concerning purpose and values embodied in the law are clarified to deduce the meaning of the law. From the conjunction of all these elements, it is possible to achieve the so-called ratio legis.

All these elements of interpretation are allowed to determine the will of the legislature. They do not exclude each other but instead complement each other.

Diagram 2: Legal Interpretation Elements

Whenever a case or legal matter is not explicitly ruled or dealt with in written law (i.e., there is a legal omission), the Portuguese legal system allows for analogical reasoning and extensive interpretation. While analogical reasoning (interpretação analógica) is used as a tool to fill gaps in the law by applying analogically another provision or several provisions that cover similar cases to the one at hand (analogia legis–article 10 of the Civil Code), extensive interpretation (interpretação extensiva) consists in an interpretation process that extends the standard meaning of the interpreted legal provision. Both introduce a certain degree of stability and predictability in the interpretation of the law.[9]

Corporative dispositions (normas corporativas) emerging from representative organisms of different moral, cultural, economic, or professional categories (e.g. professional bodies), that should not be contrary to legal imperative dispositions, are also immediate sources of law (article 1 of the Civil Code).

Custom (costume) is also regarded as a source of law in Portugal, to the extent that it is not contrary to the principle of good faith and only when the law so determines (article 3 of the Civil Code).

It should be noted that binding precedent does not exist in the Portuguese legal system. However, case law (jurisprudência), which arises from judicial decisions made by the courts, is relevant for the purposes of the uniform interpretation and application of the law (article 8, number 3 of the Civil Code) or where otherwise specified (decisions of the Constitutional Court, as per article 281, numbers 1 and 3 and article 119, number 1, g of the Portuguese Constitution).

As for equity (equidade), article 4 of the Civil Code states that courts may only decide, according to the principle of equity, when the law specifically allows it, when parties agree on it and the rights are non-disposable, or when parties have previously given their agreement.

Lastly, doctrine (doutrina) plays merely a secondary role as a source of law in the Portuguese legal system, being usually used in the interpretation or clarification of other sources of law.[10]

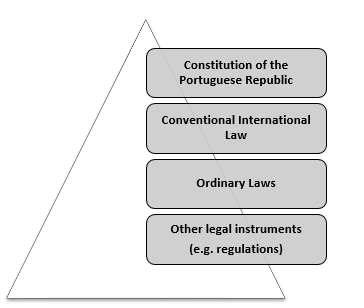

5. Main Legislation

The Portuguese legal system includes the Constitution of the Portuguese Republic and constitutional laws, which are at the top of the hierarchy of norms. The Constitution of the Portuguese Republic was approved by decree dated from April 10, 1976 (last amended by Law no. 1/2005, of August 12–seventh revision). Moreover, it comprises rules and principles of international law (jus cogens), rules set out in duly ratified or approved international agreements and issued by the competent bodies of international organisations to which Portugal belongs, as well as provisions of the treaties that govern the European Union and rules issued by its institutions (article 8 of the Constitution).

As for the Portuguese ordinary laws, they include laws (Leis) enacted by the Assembly of Republic, Decree Laws (Decretos-Lei) issued by the Government, and Regional Legislative Decrees (Decretos Legislativos Regionais) passed by the Legislative Assemblies of the Autonomous Regions of Azores and Madeira (article 112 of the Constitution). Instruments with effect equivalent to that of the laws–such as acts approving international conventions, treaties or agreements, generally binding decisions of the Portuguese Constitutional Court declaring the unconstitutionality or illegality of norms, collective labour agreements, and other collective instruments regulating labour relations–are also regarded as sources of law.

Additionally, the national legal system includes regulations or legislative instruments of lower status than laws, whose purpose is to supplement laws and fill out the details in order to be applied or implemented (e.g., regulatory decrees, regulations, regional regulatory decrees, ministerial orders, executive rulings, and municipal orders and regulations). See the European Justice, Member State law Portugal.[11]

Diagram 3: The Hierarchy of Laws

The Portuguese Civil Code, which is the basic foundation of private law (approved by Decree Law no. 47344/66, of November 25, last amended by Decree Law no. 48/2024, of July 25), is one of the most important codes in Portugal. This code revoked the first Portuguese Civil Code, also known as Seabra Code (Código de Seabra), dated from 1867.

The Portuguese legal and judicial system is a civil law system based on the Roman law traditions characterized by comprehensive law codification. The Portuguese legal system also comprises the following main (written) legislation:

- Code of Property Registry, approved by Decree Law no. 224/84, of July 6 (last amended by Law no. 45-A/2024, of December 31)

- Value Added Tax Code, approved by Decree Law no. 394-B/84, of December 26 and republished by Decree-Law no. 102/2008, of June 20 (with all subsequent amendments)

- Copyright Code, approved by Decree Law no. 63/85, of March 14 (last amended by Decree Law no. 47/2023, of June 19)

- Commercial Company Code, approved by Decree Law no. 262/86, of September 2 (last amended by Decree Law no. 114-D/2023, of December 5)

- Code of Commercial Registry, approved by Decree Law no. 403/86, of December 3 (last amended by Decree Law no. 28/2024, of April 3)

- Code of Criminal Procedure, approved by Decree Law no. 78/87, of February 17 (last amended by Law no. 52/2023 of August 28)

- Income Tax Code, approved by Decree Law no. 442-A/88, of November 30 and republished by Law no. 82-E/2014, of December 31 (with all subsequent amendments)

- Corporate Income Tax Code, approved by Decree Law no. 442-B/88, of November 30 and republished by Law no. 2/2014, of January 16 (with all subsequent amendments)

- Advertising Code, approved by Decree Law no. 330/90, of October 23 (last amended by Law no. 30/2019, of April 23)

- Road Traffic Code, approved by Decree Law no. 114/94, of March 3 (last amended by Decree Law no. 84-C/2022 of December 9)

- Criminal Code, approved by Decree Law no. 48/95, of March 15 (last amended by Law no. 15/2024, of January 29)

- Code of Civil Registry, approved by Decree Law no. 131/95, of June 6 (last amended by Decree Law no. 126/2023, of December 26)

- Notary Code, approved by Decree Law no. 207/95, of August 14 (last amended by Law no. 69/2023, of December 7)

- Expropriations Code, approved by Law no. 168/99, of September 18 (last amended by Law no. 56/2008, of September 4)

- Code of Tax Process and Procedure, approved by Decree Law no. 433/99, of October 26 (last amended by Decree Law no. 91/2024, of November 22)

- Labour Procedure Code, approved by Decree Law no. 480/99, of November 9 (last amended by Decree Law no. 87/2024, of November 7)

- Securities Market Code, approved by Decree Law no. 486/99, of November 13 (last amended by Law no. 1/2025, of January 6)

- Code of Procedure in Administrative Courts, approved by Law no. 15/2002, of February 22 (amended by Decree Law no. 87/2024, of November 7, ratified by Declaration no. 1-A/2025 of January 6)

- Military Justice Code, approved by Decree Law no. 100/2003, of November 15

- Insolvency and Company Recovery Code, approved by Decree Law no. 53/2004, of March 18 (last amended by Decree Law no. 87/2024, of November 7)

- Public Procurement Code, approved by Decree Law no. 18/2008, of January 29 (with all subsequent amendments)

- Litigation Costs Regulation, approved by Decree Law no. 34/2008, of February 26 (last amended by Decree Law no. 87/2024 of November 7)

- Labour Code, approved by Law no. 7/2009, of February 12 (last amended by Law no. 13/2023, of April 3)

- Code of Enforcement of Sentences and Measures Involving Deprivation of Liberty, approved by Law no. 115/2009, of October 12 (last amended by Law no. 35/2023, of July 21)

- New Civil Procedure Code, approved by Law no. 41/2013, of June 26 (last amended by Decree Law no. 87/2024, of November 7)

- New Administrative Procedure Code, approved by Decree Law no. 4/2015, of January 7 (last amended by Decree Law no. 11/2023 of February 10)

- Industrial Property Code, approved by Decree Law no. 110/2018, of December 10 (last amended by Decree Law no. 9/2021 of January 29)

6. Legal Professions and Organizations

The most important legal professions in Portugal are the following: judges, public prosecutors, lawyers, legal agents (or solicitors), enforcement agents, court officials, notaries, and registrars.

There are different types of judges, as follows:

- Judges of the Supreme Court of Justice and of the Supreme Administrative Court (Juízes Conselheiros)

- Judges of the Appeal Courts and of the Central Administrative Courts (Juízes Desembargadores)

- Trial Court Judges at courts of first instance and at circuit administrative courts and tax court judges (Juízes de Direito)

The High Council for the Judiciary (Conselho Superior de Magistratura) and the High Council for the Administrative and Tax Courts (Conselho Superior dos Tribunais Administrativos e Fiscais) are responsible for appointing and assigning judges to their respective courts, and for taking disciplinary action against them.

The career of the magistrates/prosecutors of the Public Prosecution Service (Ministério Público) includes the following categories:

- Prosecutor-General (Procurador-Geral da República)

- Vice-Prosecutor-General (Vice-Procurador-Geral da República)

- Deputy Prosecutor-General (Procurador-Geral Adjunto)

- District Prosecutor (Procurador da República)

- Deputy District Prosecutor (Procurador da República Adjunto)

The High Council of the Public Prosecution Service (Conselho Superior do Ministério Público) is the highest management and disciplinary body in the Public Prosecution Service and is responsible for appointing, assigning, transferring, promoting, dismissing, or removing public prosecutors from office, as well as taking disciplinary action against them.

Lawyers (Advogados) must be registered with the Portuguese Bar Association (Ordem dos Advogados Portugueses) in order to provide legal advice and represent clients before the courts. There is no distinction between practicing lawyers similar to the distinction between barristers and solicitors in some common law countries. The Portuguese Bar Association regulates the profession and takes disciplinary actions against the lawyers. According to the Pordata Data Base, in Portugal, as of 2023, there are more than thirty-six thousand registered lawyers.

Legal Agents (Solicitadores) provide legal advice and legal representation in court within the limits imposed by their statute and procedural legislation. They may represent the parties in court whenever legal representation by a lawyer is not legally mandatory, and they may also provide legal representation outside of court (e.g., before tax administration, notary offices, registrar offices, and public administration bodies).

Enforcement Agents (Agentes de Execução) do not represent any of the parties, instead they are responsible for carrying out civil enforcement activities. The Order of Legal Agents and Enforcement Agents (Ordem dos Solicitadores e dos Agentes de Execução) is responsible for regulating these professions.

Court Officials (Oficiais de Justiça) are a category of justice officials that assist in the courts and public prosecution services. The Council of Court Officials (Conselho dos Oficiais de Justiça) is responsible for assessing the professional merit of these officials and for exercising disciplinary authority over them. The CAAJ (Comissão para o Acompanhamento dos Auxiliares de Justiça) is the independent administrative entity that supervises and regulates justice assistants.

Notaries (Notaries) give legal form and public faith to legal extrajudicial acts. The Order of Notaries (Ordem dos Notários) regulates notaries’ activities jointly with the Ministry of Justice.

Registrars (Conservadores dos Registos) are public officials responsible for registering and publicizing legal acts and facts relating to immoveable property and moveable property that must be registered according to the law, as well as business activities and certain people’s life events (e.g., birth, death, and marriage). Registrars are organized in accordance with different subject areas: civil, real state, commercial, and vehicles. The Institute of Registries and Notary is responsible for implementing and monitoring register service policies in order to provide services to citizens and companies in different areas (e.g., civil identification, nationality, and passport services, as well as civil, land, vehicle, ship, commercial, and legal persons register services), and for ensuring regulation, control, and oversight of the activities of notaries.

7. Legal Education and Law Universities

Access to legal professions in general requires a law degree from a Portuguese university. Each legal profession mentioned above has its own access and admission requirements and procedures. For example, the Centre for Judicial Studies (CEJ − Centro de Estudos Judiciários) is responsible for the training of judges and public prosecutors for courts of law, while the Portuguese Bar Association is responsible for organizing and providing training to lawyers.

To obtain a law degree (licenciatura em direito), students must complete four years of study (i.e., eight semesters) corresponding to a total of 240 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS). The law degree is the first cycle of studies in the higher legal education timeline. Its main objective is to provide students with a solid legal education in all areas of law to prepare them for the professional practice of legal activities.

The second cycle, should the student pursue further higher education studies for specialization purposes, consists of the Master of Laws degree (mestrado em direito). The Master of Laws degree is accessible to holders of a law degree, and it will be achieved when the student obtains a total of 120 ECTS. Curriculums often combine an initial part of taught practical courses and then a subsequent part of research and preparation of a thesis, with the oral disseration as the final element of the master’s degree. The program usually takes two years (i.e., four semesters) to complete. Although some programs offered adopted the designation of “LL.M.,” in Portugal, the LL.M. normally corresponds to only a one-year postgrad program. The main difference with the classical master’s in laws (mestrado em direito) is that this takes two years to complete and involves the preparation and public defense of a scientific dissertation.

The third and last cycle of studies is the doctorate in law (PhD) program (doutoramento). Usually, it is accessible to holders of a master’s degree and frequently lasts three to four years (or six to eight semesters) corresponding to 180 ECTS. To conclude the doctoral degree, students must prepare an original thesis subjected to a public oral defense.

Law programs are structured according to the Bologna Process, which was implemented in Portugal in 2006-2007 and governed by Decree Law no. 74/2006, of March 24 (last amended by Decree Law no. 13/2022, of January 12). Below is a list of universities in Portugal that offer law degrees, Postgraduate Law degrees, Master of Laws degrees and Doctorate (PhD) in Law programs, as well as various other law specialization courses:

Public Universities

- Universidade de Coimbra (Faculty of Law), which is the oldest university of Portugal and one of the oldest in the world

- Universidade de Lisboa (Faculty of Law)

- Universidade do Minho (Law School)

- Universidade Nova de Lisboa (Faculty of Law)

- Universidade do Porto (Faculty of Law)

Private Universities

- Universidade Autónoma de Lisboa (Law Department)

- Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Escola de Lisboa (Lisbon School of Law)

- Universidade Católica Portuguesa, Escola do Porto (Porto School of Law)

- Universidade Lusíada de Lisboa (Lisbon Faculty of Law)

- Universidade Lusófona (Faculty of Law)

- Universidade Portucalense (Law Department)

Please note that that the above are informative lists that do not represent a ranking order.

Although Portuguese is the official language of legal studies, a number of universities have some advanced programs taught in English, such as:

- Católica Global School of Law of Universidade Católica Portuguesa

- LL.M. Law in a European and Global Context

- LL.M. International Business Law

- LL.M. Law in a Digital Economy

- Executive LL.M. Regulation and Compliance

- Master in Transnational Law (MTL)

- Global Ph.D. Programme in Law (Ph.D.)

- IJP–Portucalense Institute for Legal Research of Universidade Portucalense

- LL.M. in Transnational Business Law

- NOVA School of Law of Universidade Nova de Lisboa:

- Master in Law and Tech

- Master in Law and Management

- Master in Law and Financial Markets

- Master in Law and Economics of the Sea

- Master in Law and Security

- Master in Law–Specialization in International and European Law

- School of Law of the University of Minho

- LL.M. in European and Transglobal Business Law

8. Research Databases

Major open access research databases in Portuguese are available for consultation free of charge:

- Official Gazette (Diário da República Eletrónico − DRE) where all legislation currently in force, all amendments, and revoked diplomas are published

- Prosecutor General’s Office of Lisbon District (Procuradoria Geral Distrital de Lisboa − PGDL) has legislation and court decisions

- Bases Jurídico-Documentais from the Financial Management and Infrastructures of Justice (Instituto de Gestão Financeira e Equipamentos da Justiça − IGFEJ) with relevant case law

- Portuguese Bar Association (Ordem de Advogados) has an online research tool (LawyerSearch tool) to find lawyers currently practicing as well as lawyers whose license is inactive

- High Council for the Judiciary (Conselho Superior da Magistratura) provides lists of judges (Quadro de Juízes)

- eTribunal Citius is a tool for courts and legal practitioners by which it is possible to initiate court proceedings online, and it also provides access to useful information about legal matters

- Base: contratos públicos online provides public information on public procurement subject to the Public Procurement Code regime

- Ministry of Justice (Ministério da Justiça) provides information on publications of corporate acts and from other entities

- Portuguese Institute of Industrial Property (Instituto Nacional da Propriedade Industrial) has online research tools of trademarks, patents, and designs, among other services

Open access free of charge websites that offer non-official English translations of legislation:

- Portuguese Assembly of Republic with the Portuguese Republic Constitution, as well as other important pieces of legislation related to politico-parliamentary activities.

- Prosecutor General’s Office with a partial translation of the Code of Criminal Procedure, as well as other laws on criminal matters.[12]

- The Competition Authority (AdC–Autoridade da Concorrência) with a bilingual version of the Competition Law (Law no. 19/2012, of May 8, last amended by Law no. 17/2022, of August 17).

- National Authority for Communications (ANACOM–Autoridade Nacional de Comunicações) with translations of relevant legislation in the communications sector, the most important being the Electronic Communications Law (Law no. 16/2022, of August 16, last amended by Decree Law no. 114/2024, of December 20), which establishes the legal regime applicable to electronic communications networks and services, and the Postal Law (Law no. 17/2012, of April 26, last amended by Law no. 30/2023, of July 4), which establishes the legal regime that governs the provision of postal services.

Other relevant links with information in English:

- Bank of Portugal (Banco de Portugal) on money laundering and terrorist financing

- Portuguese Securities Market Commission (CMVM − Comissão do Mercado de Valores Mobiliários) on money laundering and terrorist financing

- Tax and Customs Authority (AT–Autoridade Tributária e Aduaneira) on tax and customs

- National Cybersecurity Centre (CNCS–Centro Nacional de Cibersegurança) on cybersecurity

- Portucalense Legal Institute (IJP–Instituto Jurídico Portucalense) on a wide range of law related subjects

9. Bibliography

Most legal books and publications are written by legal professionals in Portuguese. Some of the major legal publishers are:

Administrative Law

- Almeida, Mário Aroso de, “Teoria Geral do Direito Administrativo, o Novo Regime do Código do Procedimento Administrativo,” 11.a Edição, Almedina, 2024, Reimpressão 2023

- Amaral, Diogo Freitas do, “Curso de Direito Administrativo,” Volume I, Almedina, 2018, Reimpressão 2024 da 4.a Edição de 2015

- Andrade, José Carlos Vieira de Andrade, “Lições de Direito Administrativo,” 5.a Edição, Imprensa da Universidade de Coimbra, Coimbra Jurídica, 2020

- Caetano, Marcello, “Manual de Direito Administrativo,” Volume I, Almedina, 2016, Reimpressão 2020

- Dias, José Eduardo de Oliveira Figueiredo Dias; Oliveira, Fernanda Paula, “Noções Fundamentais de Direito Administrativo,” Almedina, 2017, 5.a Edição–Reimpressão 2023

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Neves, Ana Fernanda, Serrão, Tiago, “Organização Administrativa: Novos Actores, Novos Modelos,” Volume I, AAFDL Editora, 2018

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Neves, Ana Fernanda, Serrão, Tiago, “Organização Administrativa: Novos Actores, Novos Modelos,” Volume II, 1.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, 2018

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Pedro, Ricardo, Caldeira, Marco, Serrão, Tiago (Coord.), “Comentários ao Código do Procedimento Administrativo,” Volume I, 6.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, Lisboa, 2023

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Pedro, Ricardo, Caldeira, Marco, Serrão, Tiago (Coord.), “Comentários ao Código do Procedimento Administrativo,” Volume II, 6.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, Lisboa, 2023

- Gonçalves, Pedro Costa; Otero, Paulo, “Tratado de Direito Administrativo Especial,” Volume I, Almedina, 2017, Reimpressão da Edição de 2009

- Moncada, Luíz S. Cabral de, “Código do Procedimento Administrativo–Anotado,” Quid Juris, 2022

- Otero, Paulo, “Direito do Procedimento Administrativo I,” Almedina, 2016, Reimpressão 2024

- Quadros, Fausto (et al), “Comentários à revisão do Código do Procedimento Administrativo,” Almedina, 2022

- Vieira, Vítor Manuel Freitas, “O Novo Código do Procedimento Administrativo − Perguntas e Respostas,” Almedina, 2017

Administrative Procedure Law

- Almeida, Mário Aroso de, “Manual de Processo Administrativo,” 8.a Edição, Almedina,2024

- Cadilha, Carlos Alberto Fernandes Cadilha, e Almeida, Mário Aroso, “Comentário ao Código de Processo nos Tribunais Administrativos,” Almedina, 2021, 5.a Edição − Reimpressão 2022

Civil Law

- Costa, Mário Júlio de Almeida, “Noções Fundamentais de Direito Civil,” Almedina, 2018, 7.a Edição – Reimpressão 2023

- Pinto, Paulo da Mota, “Direito Civil–Estudos,” Gestlegal, 1.a Edição, 2021

- Pinto, Carlos Alberto da Mota Pinto, Pinto, Paulo Mota, Monteiro, António Pinto, “Teoria Geral do Direito Civil,” Gestlegal, 5.a Edição, 2020

- Prata, Ana (Coord.), “Código Civil Anotado − Vol. II Art. 1251o a 2334.o,” 3.a Edição, Almedina, 2023

- Vasconcelos, Pedro Pais de, e Vasconcelos, Pedro Leitão Pais, “Teoria Geral do Direito Civil,” Almedina, 2019, 9.a Edição–Reimpressão 2023

Civil Procedure Law

- Amaral, Jorge Augusto Pais de, “Direito Processual Civil,” 16.ª Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Carvalho, J. H. Delgado de, “Temas de Processo Civil,” Quid Juris, 2019

- Geraldes, António Santos Abrantes, “Recursos em Processo Civil,” 8.a Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Gonçalves, Marco Carvalho, “Lições de Processo Civil Executivo,” Almedina, 2022, 5.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Pimenta, Paulo, “Processo Civil Declarativo,” Almedina, 2020, 3.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Pinheiro Torres, Pedro, Pinheiro Torres Luísa, “Formulários BDJUR − Processo Civil − Procedimentos Cautelares e Requerimentos Diversos,” Almedina, 2021, 2.a Edição, Reimpressão 2023

- Pinto, Rui, “Novos Estudos de Processo Civil,” Petrony, 2017

- Rodrigues, Fernando Pereira, “Noções Fundamentais de Processo Civil,” Almedina, 2019, 2.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

Commercial Law

- Abreu, Jorge Manuel Coutinho de, “Curso de Direito Comercial − Volume I,” Almedina, 2022, 13.a Edição–Reimpressão 2023

- Abreu, Jorge Manuel Coutinho de, “Curso de Direito Comercial − Volume II − Das Sociedades,” 8.a Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Cordeiro, António Menezes Cordeiro, “Direito Comercial,” 5.a Edição, Almedina, 2022

- Cunha, Paulo Olavo, “Direito Comercial e do Mercado,” Almedina, 2021, 3.a Edição–Reimpressão 2022

- Pais de Vasconcelos, Pedro, Vasconcelos, Pedro Leitão Pais de, “Direito Comercial,” Almedina, 2020, 2.o Edição–Reimpressão 2023

- Ramirez, Paulo, “Direito Comercial,” 4.a Edição, Almedina, 2023

Compliance

- Rodrigues, André Alfar, “Manual Teórico-Prático de Compliance,” 3.a Edição, Almedina, 2023

- Rodrigues, André Alfar, “Minutas e Políticas de Compliance,” Almedina, 2024

- Fernanda Palma, Maria Silva Dias, Augusto, Sousa Mendes Paulo de, (Coord.) “Estudos sobre Law Enforcement, Compliance e Direito Penal,” 2.a Edição, Almedina, 2018

Constitutional Law

- Blanco de Morais, Carlos, “Curso de Direito Constitucional − Tomo II − Teoria da Constituição,” Almedina, 2018, Reimpressão 2022

- Canotilho, José Joaquim Gomes, “Direito Constitucional e Teoria da Constituição,” Almedina, 2018, 7.a Edição- Reimpressão 2021

- Canotilho, José Joaquim Gomes, “Constituição da República Portuguesa −Anotada − Volume I – Artigos 1.o a 107.o,” Coimbra Editora, 2014

- Canotilho, José Joaquim Gomes, “Constituição da República Portuguesa − Anotada − Volume II – Artigos 108.o a 296.o,” Coimbra Editora, 2014

- Novais, Jorge Reis, “Princípios Estruturantes de Estado de Direito,” Almedina, 2022, 2.a Edição 2023

- Otero, Paulo, “Direito Constitucional Português Volume I − Identidade Constitucional,” Almedina, 2017, Reimpressão 2022 da Edição de 2010

Criminal Law

- Costa, José Faria de, “Direito Penal,” Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 2017

- Palma, Maria Fernanda, “Direito Penal,” AAFDL Editora, 5.a Edição − Reimpressão 2023

- Prata, Ana, Veiga, Catarina, e Almeida, Carlota Pizarro, “Dicionário Jurídico, Vol II − Direito Penal e Direito Processual Penal,” Almedina, 2018, 3.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

Criminal Procedure Law

- Antunes, Maria João, “Direito Processual Penal,” Almedina, 2023, 5.a Edição–Reimpressão 2025

- Mendes, Paulo de Sousa, “Lições de Direito Processual Penal,” Almedina, 2018, Reimpressão 2024

- Silva, Germano Marques da, “Direito Processual Penal Português,” 2.a Edição, Universidade Católica, 2017

Fundamental Rights

- Andrade, José Carlos Vieira de Andrade, “Os Direitos Fundamentais na Constituição de 1976,” Almedina, 2019, 6.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Miranda, Jorge, “Direitos Fundamentais,” Almedina, 2020, 3.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Pinto, Paulo Mota, “Direitos de Personalidade e Direitos Fundamentais–Estudos,” Gestlegal, 1.a Edição, 2019

- Silva, Jorge Pereira da, “Direito Fundamentais,” Universidade Católica, 2018

Health Law

- Barbosa, Carla, Pereira, André Dias, e Loureiro, João, “Direito da Saúde I–Objeto, Redes e Sujeitos,” Almedina, 2016

- Barbosa, Carla, Pereira, André Dias, e Loureiro, João, “Direito da Saúde II–Profissionais de Saúde e Pacientes. Responsabilidades,” Almedina, Reimpressão 2020

- Barbosa, Carla, Pereira, André Dias, e Loureiro, João, “Direito da Saúde III–Segurança do Paciente e Consentimento Informado,” Almedina, 2016

- Barbosa, Carla, Pereira, André Dias, e Loureiro, João, “Direito da Saúde IV–Genética e Procriação Medicamente Assistida,” Almedina, 2016

- Barbosa, Carla, Pereira, André Dias, e Loureiro, João, “Direito da Saúde V –Saúde e Direito: Entre a Tradição e a Novidade,” Almedina, 2016

- Macieirinha, Tiago, e Estorninho, Maria João, “Direito da Saúde–Lições,” Universidade Católica, 2014

Intellectual and Industrial Property Law

- Ascenção, José de Oliveira, e Vicente, Dário Moura, “Direito da Propriedade Industrial,” 3.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, 2019

- Gonçalves, Luís Manuel Couto, “Manual de Direito Industrial,” 11.a Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Mello, Alberto de Sá, “Manual de Direito de Autor e Direitos Conexos,” 6.a Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Nunes, Pedro Miguel Duarte, “A Inteligência Artificial e o Direito da Propriedade Intelectual,” Almedina, 2023

- Pereira, Alexandre Dias, “Direito da Propriedade Intelectual & Novas Tecnologias–Estudos,” Vol. I, Gestlegal, 1.a Edição, 2019

Introduction to the Study of Law

- Ferreira, José António Gonçalves, Pereira, António Garcia, e Falcão, David, “Introdução ao Direito,” Almedina, 6.a Edição, 2024

- Sousa, Miguel Teixeira de, “Introdução ao Direito,” Almedina, 2018, Reimpressão 2023

Labour and Social Security Law

- Abrantes, José João, “Estudos de Direito do Trabalho,” 3.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, 2018

- Barros, Mário Silvério de, “Direito da Segurança Social,” Almedina, 2024

- Conceição, J. B. Apelles, “Segurança Social–Manual Prático,” 14.a Edição, Almedina, 2023

- Falcão, David, e Tomás, Sérgio Tenreiro, “Lições de Direito do Trabalho–A Relação Individual do Trabalho,” 14.a Edição, Almedina, 2025

- Fernandes, António Monteiro, “Direito do Trabalho,” Almedina, 2023, 22.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Martinez, Pedro Romano, “Direito do Trabalho,” Almedina, 2023, 11.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Neto, Abílio, “Código do Trabalho e Legislação Complementar Anotados,” Ediforum, 2019, 5.a Edição–Reimpressão 2020

- Leitão, Luíz Manuel Teles de Menezes, “Direito do Trabalho,” Almedina, 2023, 8.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Leite, Fausto, “Formulários BDJUR–Laboral,” Almedina, 2023, 9.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

Law of Obligations

- Costa, Mário Júlio de Almeida, “Direito das Obrigações,” Almedina, 2010, 12.a Ediçãp–Reimpressão 2024

- Leitão, Luís Manuel Teles de Menezes, “Direito das Obrigações − Vol. I,” Almedina, 2022, 16.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Leitão, Luís Manuel Teles de Menezes, “Direito das Obrigações − Vol. II,” Almedina, 2021, 13.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Leitão, Luís Manuel Teles de Menezes, “Direito das Obrigações − Vol. III,” Almedina, 2022, 14.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Prata, Ana “Lições de Direito das Obrigações,” Almedina, 2024

- Quintas, Paula, “Manual Prático de Direito das Obrigações,” 5.a Edição, Almedina, 2023

Public Finances and Tax Law

- Azevedo, Maria Eduarda, “Manual de Finanças Públicas e Direito Financeiro,” Quid Juris, 2018

- Catarino, João Ricardo, “Finanças Públicas e Direito Financeiro,” 9.a Edição, Almedina, 2024

- Pereira, Paulo Trigo e Nunes, Francisco, “Economia e Finanças Públicas–Da Teoria à Prática,” Almedina, 2020, 6.a Edição–Reimpressão 2022

- Gameiro, António Ribeiro, Costa, Belmiro Moita da, e Costa, Nuno Moita da, “Finanças Públicas,” Almedina, 2018

- Sousa, Domingos Pereira de, “Finanças Públicas e Direito Financeiro,” Volume I / Volume II , Quid Juris, 2017

Public Procurement

- Dores, Jorge, “Guia do Gestor do Contrato na Contratação Pública,” 3.a Edição, Edições Sílabo, 2025

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Pedro, Ricardo, Caldeira, Marco, Serrão, Tiago (Coord.), “Comentários ao Código dos Contratos Públicos,” Volume I, AAFDL Editora, Lisboa, 2024

- Gomes, Carla Amado, Pedro, Ricardo, Caldeira, Marco, Serrão, Tiago (Coord.), “Comentários ao Código dos Contratos Públicos,” Volume II, AAFDL Editora, Lisboa, 2024

- Gonçalves, Pedro Costa, “Direito dos Contratos Públicos,” Almeida, 2023, 6.a Edição–Reimpressão 2024

- Oliveira, Rodrigo Esteves de, e Oliveira, Mário Esteves de, “Concursos e outros Procedimentos de Contração Publica,” Almedina, 2016

- PLMJ Advogados, “Código dos Contratos Públicos e Medidas Especiais de Contratação Pública,” Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda, 2022

- Raimundo, Miguel Assis, “Direito dos Contratos Públicos − Volume 1 − Introdução. Regime de Formação,” AAFDL Editora, Lisboa, 2022, Reimpressão 2023

- Raimundo, Miguel Assis, “Direito dos Contratos Públicos − Volume 2 − Regime Substantivo,” AAFDL, Lisboa, 2022, Reimoressão 2023

- Sánchez, Pedro Fernández, “Estudos sobre Contratos Públicos,” AAFDL Editora, 2019

- Silva, Jorge Andrade da Silva, “Dicionário dos Contratos Públicos,” Almedina, 2018, 2a Edição − Reimpressão 2020

- Silva, Jorge Andrade da Silva, “Código dos Contratos Públicos − Comentado e Anotado,” 12a Edição, Almedina, 2024

Regulation

- Ferreira, João Pateira, Cabugueira, Manuel, Moura, e Silva Miguel, Castro Marques, Nuno, Lopes Marcelo, Paulo, “Manual de Regulação e Concorrência,” Almedina, 2024

- Gomes, Carla Amado; Pedro, Ricardo; Saraiva, Rute; Maçãs Fernanda (Coord.), “Garantia de Direitos de Regulação: Perspetivas de Direito Administrativo,” AAFDL Editora, 2024 Reimpressão

- Gonçalves, Pedro “Regulação, Electricidade e Telecomunicações,” Coimbra Editora, 2008

- Gonçalves, Pedro Costa (organização), “Estudos de Regulação Pública − II,” Coimbra Editora, 2015

- Moncada, Luiz Cabral de, “Direito da Regulação Económica,” Almedina, 2024

- Moreira, Vital de (organização), “Estudos de Regulação Pública − I,” Coimbra Editora, 2004

Urban Planning and Environment Law

- Carvalho, Raquel, “Introdução ao Direito do Urbanismo,” 4.a Edição Universidade Católica, 2024

- Condesso, Fernando dos Reis, “Direito do Ambiente − Ambiente e Território. Urbanismo e Reabilitação Urbana,” 3.a Edição, Almedina, 2018

- Gomes, Carla Amado, “Introdução ao Direito do Ambiente,” 6.a Edição, AAFDL Editora, 2023

- Oliveira, Fernanda Paula, “Escritos Práticos de Direito do Urbanismo,” Almedina, 2017

- Miranda, João, “Estudos de Direito do Ordenamento do Território e do Urbanismo,” AAFDL Editora, 2016

Moreover, there is a considerable number of periodical publications. Below is a non-exhaustive list of legal journals and periodicals, in Portuguese, by subject:

- Boletim da Faculdade de Direito

- Cadernos de Direito Privado | Cejur

- Cadernos de Justiça Administrativa | Cejur

- Cadernos de Justiça Tributária | Cejur

- Católica Law Review

- E-Pública – Revista Eletrónica de Direito Público

- Lex Familiae – Revista Portuguesa de Direito da Família

- Lex Medicinae – Revista Portuguesa de Direito da Saúde

- Revista da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade do Porto

- Revista de Finanças Públicas e Direito Fiscal

- Revista da Ordem dos Advogados

- Revista de Concorrência e Regulação

- Revista de Contratos Públicos

- Revista de Direito Administrativo

- Revista de Direito Civil

- Revista de Direito Comercial

- Revista de Direito da Responsabilidade

- Revista de Direito Financeiro e dos Mercados de Capitais

- Revista de Direito Intelectual

- Revista da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade de Lisboa

- Revista de Legislação e de Jurisprudência

- Revista de Legubus – Faculdade de Direito Universidade Lusófona

- Revista Direito do Desporto

- Revista Direito e Justiça

- Revista do Centro de Estudos Judiciários

- Revista do Ministério Público

- Revista do Tribunal de Contas

- Revista Eletrónica de Direito

- Revista Eletrónica de Fiscalidade

- Revista Intenacional de Arbitragem e Conciliação

- Revista Portuguesa de Ciência Criminal

- Revista Themis da Faculdade de Direito da Universidade NOVA de Lisboa

- Undecidabilities and Law – The Coimbra Journal for Legal Studies

Some Law Firms also have publications (e.g., newsletters, papers and articles) of legal interest in English:

- Abreu

- Garrigues

- DLA Piper ABBC

- Linklaters

- Miranda

- Morais Leitão Galvão Teles, Soares da Silva & Associados

- Uría Menéndes Proença de Carvallho

- VdA – Vieria de Almeida

[1] Rodrigues, António Simões, “História de Portugal em Datas,” Edição Círculo de Leitores, 1994.

[2] Saraiva, José Hermano, “Portugal, A Companion History,” Carcanet, 2012.

[3] All citations of the Portuguese Republic Constitution in this article are from the English translation edition, available at the website of the Portuguese Official Gazette.

[4] Weatherill, Stepen, and Beaumont, Paul, EU Law, “The essential guide to the legal workings of the European Union,” Pinguin Books, 1999.

[5] Moreira, Vital, e Maçãs, Fernanda, “Autoridades Reguladoras Independentes, Estudo e Projeto de Lei-Quadro,” Coimbra Editora, 2003.

[6] The Bank of Portugal was established by Royal Charter on November 19,1846.

[7] AdC has regulatory powers on competition over all sectors of economy including the regulated sectors.

[8] Moniz, Carlos Botelho, e Melo, Pedro de Gouveia, “The New Framework Law on Independent Regulatory Atuhotiries in Portugal,” European Public Law 21, number 1 (Kluwer Law International BV 2015), 3-30.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Neto, Abílio, “Código Civil, Anotado,” 20.a Edição Actualizada, Ediforum 2021, Reimpressão 2022. See also, Ascensão, José de Oliveira, “O Direito, Introdução e Teoria Geral,” Almedina, 2017, 13.a Edição––Reimpressão 2024.

[11] Canotilho, José Joaquim Gomes, “Direito Constitutional e Teoria da Constituição,” Almedina, 2018, 7.a Edição – Reimpressão 2021.

[12] For a partial translation into English of the Portuguese Criminal Code (dated from 2006), see the Portuguese Penal Code, General Part (Articles 1-130).